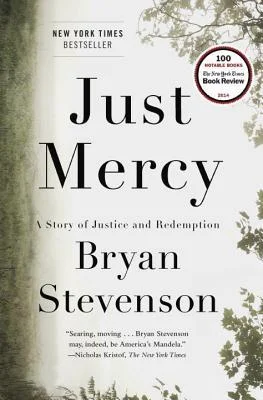

Have you ever heard the words of someone whose convictions are so simple and so profound, that they come out like poetry? Where the words march with an inner beat that find their way into the cadence of your own heart? And even when the final sentence has been read and the book closed, the words remain with you, beating and marching on? Last month, James and I read Just Mercy together and we can still feel Bryan Stevenson's words.

Bryan takes his readers through the astonishing realities of a broken criminal justice system in our country where:

+ the U.S. prison population has grown from 300,000 to 2.4 million in the last 40 years,

+ the U.S. has the highest incarceration rate in the world,

+ the death penalty in America is defined by bias, error and unreliability, and where

+ a perpetrator is 11 times more likely to be sentenced to death if the victim is white than if the victim is black.

Just Mercy follows Bryan's journey as a young lawyer working in Montgomery, AL and the people he has tirelessly fought on behalf of over the years. His stories elicit the deepest sense of injustice, a grief of the world's wrongs and a sinking feeling of implication - and yet - through his careful guiding, Bryan leads us on his way with the tenacity for hope. He believes we must protect our hope, proclaiming that hopelessness is the beginning of injustice. Hope, he says, gets you to stand up when everyone tells you to sit down. Hope is essential, and it takes courage to be hopeful.

courtesy: eji.org

In Just Mercy, Bryan recalls the story in the Bible when a woman accused of adultery was brought to Jesus, and he told the accusers who wanted to stone her to death, "Let he who is without sin cast the first stone." The accusers left and Jesus forgave her and urged her to sin no more. Bryan writes,

"Today, our self-righteousness, our fear, and our anger have caused even the Christians to hurl stones at the people who fall down, even when we know we should forgive or show compassion. I told the congregation that we can't simply watch that happen. I told them we have to be stonecatchers."

To be a stonecatcher, according to Bryan, is to be willing to do uncomfortable things. And that's hard. And sometimes you have to choose it. Sometimes, he says, you've got to stand up for something and be a witness.

This week I was in Oxford with James for the Skoll World Forum where Bryan was awarded the prestigious Skoll Award for Social Entrepreneurship for his work with the Equal Justice Initiative. Under his leadership, EJI has successfully exonerated innocent death row prisoners, protected the rights of minors and the mentally ill, and recently won a historic ruling at the US Supreme Court banning mandatory life-without-parole sentencing for all children under 17 years of age as unconstitutional. And even though it hurts to catch all those stones, he marches on.

“Why do we want to kill all the broken people? Why do we want to stomp on the broken? I do what I do because I believe that I am broken, too. There’s a power in the broken.”

The $1.25M core support investment from the Skoll Foundation will focus on scaling and increasing the impact of Bryan and Equal Justice Initiative's crucial work in building a just criminal system.

The hope, too, is that awards like these amplify Bryan's voice, and that the voice would not just resonate, but that it would move more people and transform broader systems toward a more just society.

And that kind of transformation will require more than tweeting his profound statements, more than dog-earing the pages of his book.

It will require that the beats of our own hearts march alongside the convictions of those words, and that we seriously examine our own judgements and failures to act or speak up.

It will demand that we do more than heroize those who do the work of justice.

And, it will insist that you and I don't leave it to Bryan Stevenson and EJI to be the only stonecatchers.

We've got to be them, too.

Skoll Awardees Vivek Maru, Chuck Slaughter, Bryan Stevenson, Skoll Foundation CEO Sally Osberg, Jeff Skoll, and Skoll Awardees Mallika Dutt, Oren Yakobovich and Sonali Khan.